“Democracy’s intrinsic value implies a need to focus on participation as a process.” Those words from a recent Civicus report call to mind the growth and need of democratic mechanisms that invite more public involvement than traditional forms of democracy.

Indeed, research from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace finds that in recent years, European governments, international organizations, civil society bodies, and citizens themselves have embraced the notion of participatory governance.

Participatory governance, as defined by the Oxford Handbook of Governance, “seeks to deepen citizen participation in the governmental process by examining the assumptions and practices of the traditional view that generally hinders the realization of a genuine participatory democracy.”

In more simple terms, participatory government is engagement into a decision-making process. And more broadly speaking, participatory governance can encompass activities that inform the public about government policies or decisions, educate the public about their rights and responsibilities, or even monitor public services.

For example, participatory governance can take the shape of citizen assemblies to discuss various local and national issues, from gender issues to climate change, political challenges, and even the future of the European Union. And the composition of forms of participatory government are evolving to include experts and require that authorities adopt the decisions of assemblies’ results.

Proponents of participatory mechanisms of government laud them as a fresher form of democracy, providing citizens with an outlet to voice their frustrations and impact policymaking, countering waves of illiberal populism that have swept across the world.

But Senior Carnegie Fellow, Richard Youngs, writes in “Can Citizen Participation Really Receive European Democracy?,” that participatory democracy must continue to evolve. As governments’ push to adopt more mechanisms, it will be crucial to ensure that they are truly deliberative and include adequate participation levels, and for permanent citizens’ groups and committees (as opposed to ad hoc groups) to regularly provide input on policy issues, national identity, and involvement in high politics. And moreover, participative efforts must not undercut simultaneous progress and relations with political representatives.

While participatory democracy offers great promise, Youngs cautions that merely introducing more participatory processes is not a panacea—for example, the processes could be manipulated by leaders for undemocratic purposes—and encourages governments to widen participative forums by increasing their political relevance without undermining the forums more practical features.

The sobering reality is that even in places with successful [participatory governance] initiatives, this has not sufficed to stem illiberal macro-level political trends.

Richard Youngs

The States of Ukrainians’ Participation in Governance

What are Ukrainians’ current perceptions about forms of participatory democratic activities that are available to them?

Engagement is at the core of the USAID/ENGAGE activity in Ukraine, aiming to increase citizen awareness of and engagement in civic activities at the national, regional, and local level. Awareness is a necessary requirement for participatory governance. Without knowledge of decision-making processes, one’s rights, and the impact of policy, citizens may lack the information they need to act in their best interests and further risk being manipulated by corrupt politicians or populists. If fact, participatory governance tools themselves could be used for undemocratic purpose without some level of civic literacy.

Results from the USAID/ENGAGE National Civic Engagement Poll, conducted in January 2020, indicate that the vast majority of Ukrainians are both inactive and disinterested in various forms of participatory governance.

For example, 37% of respondents of the National Civic Engagement Poll indicate that they do not have time to participate in CSO organized activities, while another 47% indicate that they do not have interest to do so. Lack of interest even extends to some forms of participatory governance activities that directly impact the polls’ respondents, such as local housing issues. There are likely several factors behind this disinterest. Lack of trust is considered by experts to be an issue impacting participation. Given that 79% of Ukrainians see the government as ineffective in fighting corruption, a lack of trust in institutions likely contributes to limited participation, disinterest, and a lack of empowerment. Awareness could contribute as well, at least for some forms of participation. Respondents expressed only limited awareness of activities such as participation in public hearings (54%), the initiation and signing of electronic petition regional and national authorities (51%), online anonymous reports on corruption or violations at elections (46%), and even less knowledge of engagement in commenting on local or national draft laws (39%) or participation in formal advisory bodies a the local or national level (39%).

Only 4-8% of Ukrainians indicated that they had participated in a single action from a list of over a dozen various activities, ranging from signing petitions, filing a complaint, requesting information from the government, or attending an assembly. Of the few that did participate, most participants seemingly participate in activities that directly impact their day-to-day lives, such as creating a committee to address their neighborhood housing issues (8%).

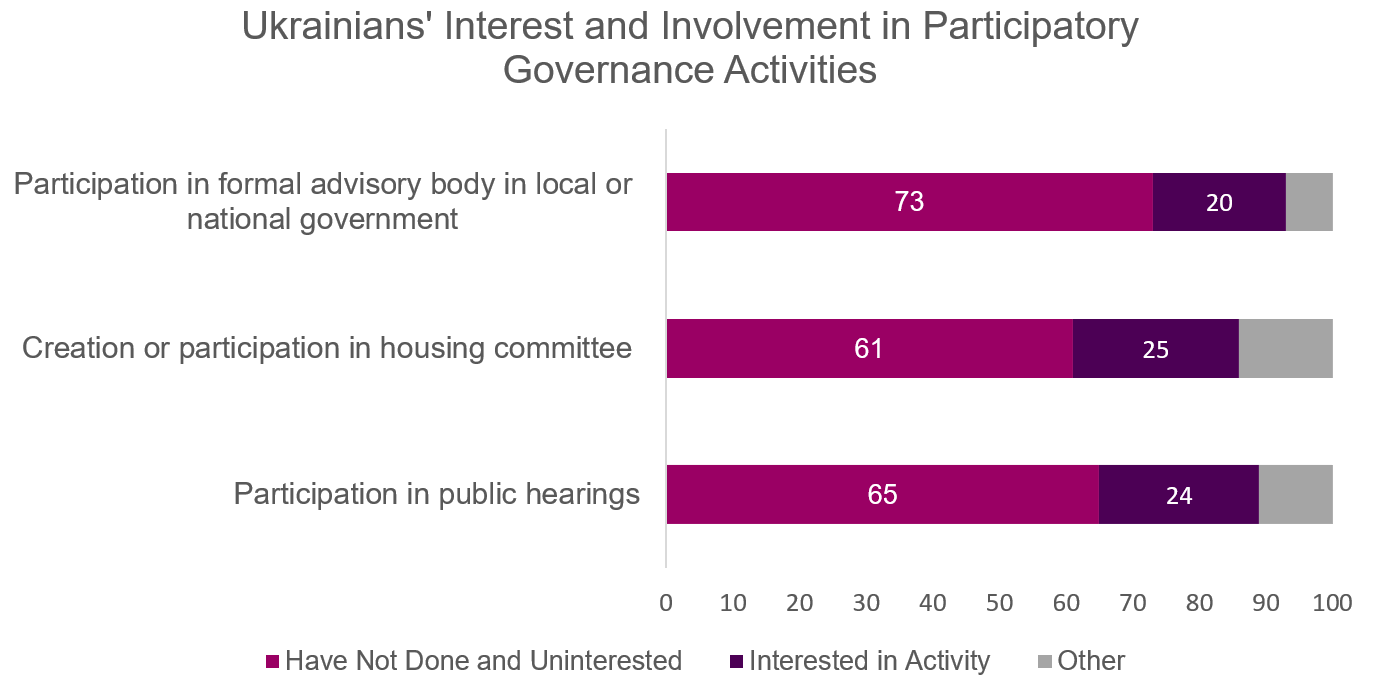

As the below figure shows, 65% respondents indicated that they had not participated in public hearings and were not interested in doing so, while only 24% reported that they had interest in doing so. Similar rates are observable in citizen participation in formal advisory bodies and housing committees, where 73% and 61% indicated that they had not participated in those activities and were not interested in doing so, respectively.

Approximately 20% of respondents indicated that they had an interest in participating in a formal advisory board in local or national government, while a slightly higher rate of 25% were interested in participating in the committees concerning their housing issues, and 24% expressed interest in participating in more general public hearings.

In order to stimulate Ukrainians’ interest levels and connect citizens with opportunities to become involved in local and national processes, civil society organizations are introducing their own participatory governance activities. USAID/ENGAGE and partner civil society organizations are connecting with citizens in various ways—in the classroom, through interactive games, at high-level conferences, and in local town halls—to amplify their voices in participatory governance.

For example, at the national level, committees are being created to link civil society voices to public officials. This past fall, civil society representatives assembled with government officials to discuss better participation and governance at an event titled PlatForum. The event increased the capacity of Ukrainian civil society for participatory governance in the new political environment through committees such as the Public Integrity Council, a permanent council linking civil society with the public sector.

At the regional level, efforts are also underway to connect Ukrainians with European integration processes as a part of ongoing decentralization reforms. The New Europe Center, a USAID/ENGAGE partner, finds that authorities’ increased attention to the expectations of local communities that attach when civil society actors become involved and the increased accountability citizens hold over their representatives.

Various forms of participatory governance activities are also emerging to address community issues, such as participatory budgeting, currently taking place from Eastern to Western Ukraine, attuning locals to the importance of democracy and how to ensure that their voices and priorities are represented. USAID/ENGAGE partner, “Development Together” envisions participatory budgeting as a tool of democratic growth that citizens can use to support their own initiatives and the organization is currently working to implement a mechanism in Kharkiv. And the Centre for United Actions has recently held participatory budgeting sessions in the region of Chermerovetsk (Khmelnytskyi Oblast), with the aim to introduce public budgeting that is open and inclusive, enabling residents from the age of 14 to take part.

Civicus also notes the importance that tools like civic education plays in bringing Ukrainians closer to political decision-making processes. Teaching both students and adults about the importance of active citizenship, through both formal and non-formal means—such as the new mandatory “3D Democracy” course for eleventh graders or an adult civic literacy test—helps citizens understand their role in democratic processes and encourages participation. Without the core foundational knowledge of their duty and rights, citizens are logically less inclined (or interested) in participating.

Despite these ongoing efforts, with such low levels of participation and interest, one might wonder, how Ukraine citizens can become more active in participatory governance and what steps can civil society and the government take?

Steps Forward to Improving Participatory Governance: A Continuing Role for Civil Society

Governance experts are calling on civil society organizations and the public sector to continue to strengthen participatory governance mechanisms in Ukraine and around the world.

And as if implementing and building effective participatory mechanism is not difficult enough, the new post-COVID-19 environment further challenges efforts to bring citizens together through quarantine restrictions and less open forms of government decision-making. A recent article from Apolitical presents research from the World Health Organization, demonstrating that governments’ listening to the community through consultations or assemblies is one of the most important things a government can do in such crises.

Analysis from VoxUkraine, a USAID/ENGAGE partner, also indicates that to address distrust, higher levels of governmental legitimacy is key and that an important source of legitimacy is democratic process. According to the article, “people support their leaders’ policies and decisions when they feel they can influence the process and that these are their own decisions as well.”

Adopting participatory governance mechanisms is certainly not an overnight endeavor, but rather an ongoing process, requiring regular growth, engagement, and knowledge of civic duty to produce new levels of political culture. To continue to increase Ukrainians’ interest in participatory governance, who are both capable of voicing opinions and influencing governance structures that impact their lives at the local and national level, civic education, public committees, and activities such as participatory budgeting must grow simultaneously and attract more participants. Continued civil society efforts in this sphere will be crucial to this process and ensuring that active citizenship become a reality of democratic governance.