The World Justice Project’s (WJP) Rule of Law Index 2020, provides an analysis of the “rule of law” across the world, including in Europe and Ukraine. The findings help all citizens and civic actors to better understand Ukraine’s strengths and weakness in governance, and identify important policy issues such as corruption, judicial independence, and enforcement matters that have affected citizens and civil society organizations.

Besides working to improve the lives of everyday Ukrainians, civil society plays an important role in participating in governmental processes to reform judicial and legal systems. One need only look to the ongoing efforts of USAID/ENGAGE partners, such as the Centre of Policy and Legal Reform, which actively monitors the constitutionality of judicial reforms impacting civil society’s participation in judicial appointment processes, or Transparency International and the Anticorruption Action Center, whose initiatives during the last year have advocated for civil society organization protections.

The Rule of Law Index Methodology

So, what is the “rule of law?” The term itself has bloomed into its own field of study among scholars, legal experts and policy-makers, and its definition remains contested. The WJP defines the rule of law as a durable system of laws, institutions, and community commitments that delivers four universal principles: accountability, just laws, open government, and access and impartial dispute resolution. According to the WJP, effective rule of law reduces corruption, combats poverty and disease, and protects people from injustices. It is also a principle in its own right, reminding us that no one is above it.

Quantifying and effectively measuring a state’s rule of law levels, its progress, and decline, is a complex and contentious endeavor. Rule of law rankings do draw criticisms from legal scholars who argue that scores are prone to inaccurately capture the breadth of legal realities in a country. In creating the Rule of Law Index, the WJP assesses each country with a rule of law score, making the Index the largest rule of law study. In the latest 2020 Index, 128 countries and jurisdictions in total were assessed, including Kosovo and Gambia. The Index draws from an impressive body of data, incorporating the voice of the general population, including 130,000 interviews and 400 expert opinions.

A country’s Rule of Law Index score ranges from 0-1, where “1” indicates the strongest levels of rule of law and a score of “0” indicates the absence of rule of law. The Index score is comprehensive in that it is composed of eight different factors, desegregating into 44 soft factors. The eight core factors include: Constraints on Government Powers, Absence of Corruption, Open Government, Fundamental Rights, Order and Security, Regulatory Enforcement, Civil Justice, and Criminal Justice.

A Pattern of Global Declines in Rule of Law

On a macro-level, the WJP Rule of Index 2020 and experts voices note continued rule of law stagnation across the world. The report notes that for a third year in row, “more countries have declined than improved in overall rule of law performance” and “[i]n every region, a majority of countries slipped backward or remained unchanged in their overall rule of law performance” during the last year. These and other WJP insights are detailed in the 2020 World Justice Project report. Speaking at the release of the Index, the Director of the WJP, Elizabeth Anderson, noted that the global negative trends are found not just in the usual suspects, including autocratic, conflict torn, and failed states, but in countries with higher incomes as well. The main drivers of decline in the scores were recorded across the component of “Constraints on Government Power.”

Turning towards Europe, the new report finds that rule of law generally remains strong. But during the last year, over half of European countries showed declines, most notably Hungary and Poland, where declines were observed in fundamental rights. Regionally speaking, Moldova made notable improvements in the rule of law. Anderson notes that the declines require government intervention and that eyes will turn to the EU for institutional responses. For example, rule of law developments in Eastern Europe have prompted an EU rule of law monitoring mechanism in Brussels. But interestingly, Ukraine has not followed the downward trend of its regional partners.

The State of Rule of Law in Ukraine: Struggles with Corruption, Civil Society’s Impact

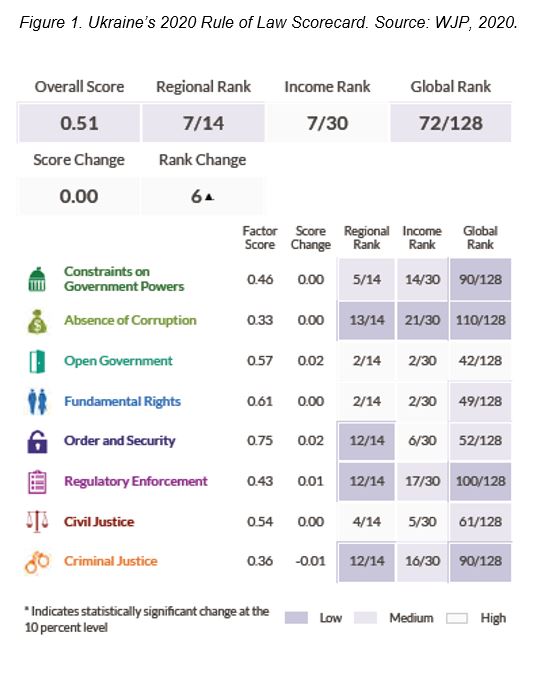

While Ukraine’s aggregate rule of law score did not decrease, it still leaves much room for improvement. Ukraine now ranks 72 out of 128 countries in the Rule of Law Index, improving its overall score by six places in 2020.

With an overall score of .51 out of 1, Ukraine still lags behind the global average score of .56. A breakdown of each of the eight rule of law factors is found in Figure 1.

As the Figure 1 demonstrates, Ukraine scores poorest in the category of “Absence of Corruption” (.33 of 1) and quite poorly in “Regulatory Enforcement” (.43 of 1) as well. Interestingly, Ukraine scored strongest in the indicator of “Order and Security”; however, while its performance in that category is high relative to countries of similar income-levels, the score is considered average at the global level and low at the regional level.

Results from the USAID/ENGAGE Civic Engagement Poll tend to support the WJP findings, particularly with respect to the corrosive effect that corruption has on a country’s rule of law. During the last year, 67% of respondents indicated that corruption levels had remained the same and another 16% stated that the levels had increased. The overwhelming majority of respondents (79%) felt that the government was ineffective in fighting corruption.

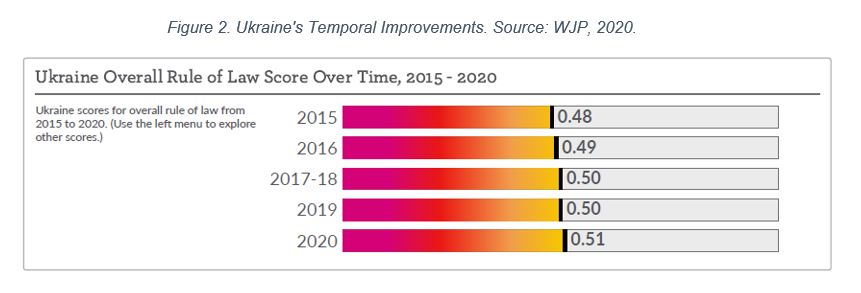

Relative to its regional neighbors in Eastern Europe and Eurasia, Ukraine modestly ranks 7 out of 14 countries; however, it did not follow the trend of neighbors who saw decreases in their rule of law scores. In fact, Ukraine has actually made modest progress. Following the Revolution of Dignity, the country has made slow but gradual improvement in its overall score. See Figure 2. As Figure 2 indicates, Ukraine’s score has slightly improved from .48 to .51 over the last six years.

Indeed, the USAID/ENGAGE Civic Engagement Poll results suggest that Ukrainians, to an extent, value the rule of law. The majority of respondents (66%) do not agree that ordinary citizens have a right to not observe laws even if public servants do” and most Ukrainians (90%) agree that a good citizen should always observe and abide by laws.

Hence, while corruption has remained a major challenge and was actually deemed to have worsened in Ukraine in that respective factor, other factors, such as “Open Government,” have improved. The factor of “Open Government”—consisting of the sub-factors of “Publicized Laws and Governmental Data,” “Right to Information,” “Civic Participation,” and “Complaint Mechanisms”—mirrors a USAID metric utilized in its Journey to Self-Reliance Roadmap, capturing open and accountable governance wherein a country’s laws and policies support progress towards self-reliance. Ukraine’s improvement in this factor may very well be attributable to civil society efforts, and the general population’s demand for law, providing some room for optimism about the results of engagement and civic participation.

For example, within the factor of “Open Government,” a score that has improved in rank in the latest Index, Ukraine receives a particularly high score in the sub-factor of “Civic Participation.” The “Civic Participation” score of .59 of 1 makes Ukraine the second strongest state in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (ranked 2 out of 14 countries).

Rule of law watchers, such as Olga Burlyuk, view civil society’s enduring demand for change as a constraint on ruling elites. Burlyuk notes that within Ukraine, “demand for law” might be further shaped and advanced via civil society engagement in awareness raising and capacity-building, which would enforce those structures that push reforms.

Ukraine’s civil society sector has also likely impacted Ukraine’s higher score in providing non-government checks on government powers, a sub-factor of the “Constraints on Government Powers,” scoring .61 of 1, second in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. WJP experts have monitored developments in Ukraine and have commended Ukraine’s civil society actors for its efforts to ensure transparency, one indicator in the Rule of Law Index. For example, speaking at an Index launch event, Joe Foti, of the Open Government Partnership, mentioned the work of reformers including ProZorro and DoZorro. Foti stressed the importance of Ukraine’s civil society actors and called for more data in studying the gaps in governance so that effective policy reforms could be implemented. And additionally, Ukrainian civil society organizations will play an important role in combating the closure of civic space in years ahead, which could jeopardize the rule of law.

Ukraine’s latest rule of law scorecard demonstrates that it continues to underperform in factors such as Corruption, along with Regulatory Enforcement, Criminal Justice, and Constraints on Government Power. Efforts to hold the government accountable on these issues can go only be so effective without political will. However, civil society’s progress in defending their rights to operate their organization and freely report and comment on government policies, so as to inform and engage the broader public, is undoubtedly a necessary and powerful force for change. In doing so, civil society organizations continue to demand and advance the rule of law in Ukraine.